[ad_1]

“I think the respect that he was afforded was, in some quarters, begrudgingly or grudgingly given.”

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photo: Getty

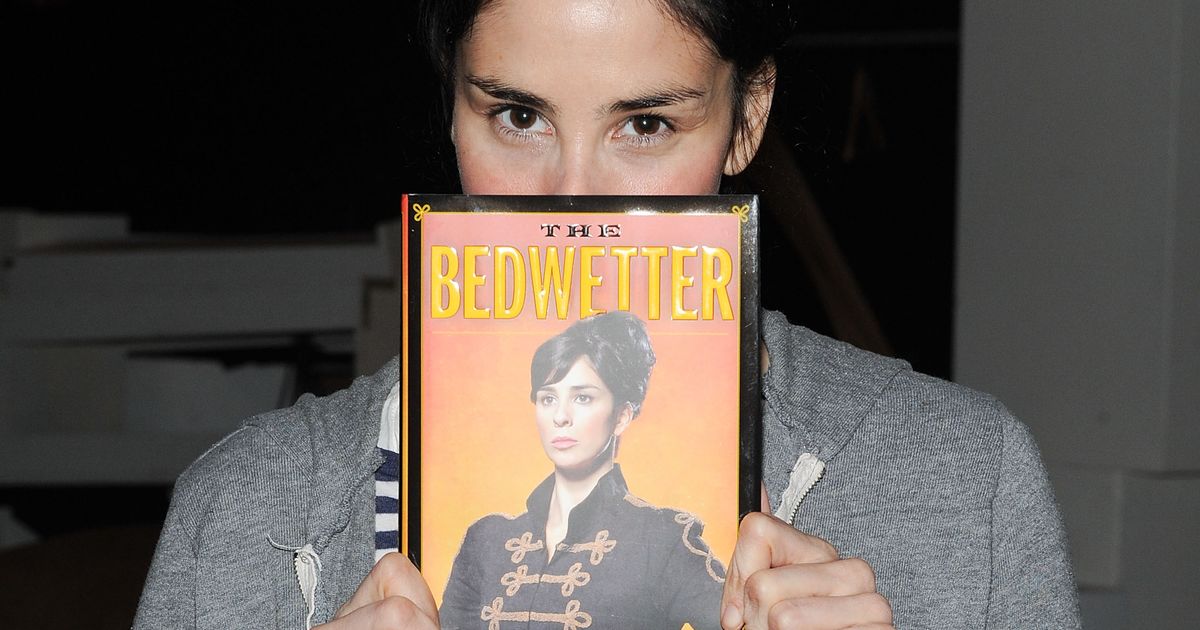

I’m about halfway into a conversation with Andrew Ridgeley when he drops a really, really, ridiculously good-looking revelation: He’s never seen Zoolander. This simply won’t do.

We’ve gathered, ostensibly, to discuss the legacy of George Michael at a significant triad of his late friend and bandmate’s career. The retrospective collection Wham! The Singles: Echoes From the Edge of Heaven was released in July alongside the buoyant Netflix documentary Wham!, and Michael is set to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame later this year after securing a landslide victory in the fan vote. But despite four decades of being a steward for the duo’s history, Ridgeley now gets to experience something new for a change: watching the aughts-defining moment when Ben Stiller, as Derek Zoolander, drinks orange-mocha frappuccinos with his model frenemies as “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” plays over their gasoline car fight. Three of them immediately die — don’t light up a cigarette at the pump, kids — but who cares? They got to go out listening to the best Wham! song of all time. “Outstanding. I love that sort of nonsense. That’s magnificent stuff,” Ridgeley says, mid-chuckle, when the clip ends. “It’s nice that people will always associate it with self-immolation.”

Ridgeley and Michael met as schoolmates and went on to forge their respective identities through the success of Wham! in the 1980s. Though Michael (or “Yog,” his childhood nickname) eventually took over full songwriting and producing duties, through it all, Ridgeley remained his idol. “Almost everything came from Andrew,” Michael says in Wham! archival footage. “Andrew changed my life in exactly the way someone needed to change my life if I was going to be a pop star.” When Wham! disbanded in 1986, leaving behind three playful and socially resonant albums, Michael became one of the best-selling musicians of all time while Ridgeley enjoyed a quiet life in Britain. Some artists may have let enduring resentment fester due to being overshadowed by their best mate, but Ridgeley defied the potential ego. During our chat, he cheerfully sat in the shade, drink in hand, discussing his late collaborator’s legacy.

His personal favorite, “You Have Been Loved,” might be the track I’d choose to fully express to someone the breadth of his artistic genius. It’s the way that he defined his art, his record-making, and the artist he ultimately became. It contains every aspect of what was best about him, which is that he gave all of himself in his music. He was a supernova in a firmament of shining stars. That’s how I would describe his position in the pantheon of greats. It’s the breadth of his songwriting skill, the way he expressed his art, his perspective of the world and of his place in it, his relationship to it, to others, his songwriting, his voice. It was possibly unrivaled.

The track I like to play and listen to most is “Amazing.” I think that could’ve quite easily been a Wham! track if we had chosen to develop into adulthood. It’s such a wonderful and uplifting pop record with a proper bittersweet lyric at the heart of it. Although its ultimate sentiment is quite joyous, the physical effect it exerts is also fabulous. It’s such a beautifully made and expressed song. I remember when he gave me the Patience CD before its release, and I played it back to back for the duration of the journey from my home in the southwest of England to London, which is about four and a half hours. “Amazing” was the sole piece of music that I played for the four and a half hours on repeat — listening to every note and every vocal inflection. It’s the perfect pop song.

I don’t think there was one song, because we knew how to make records from the very start. Even our demo recordings are fully formed. “Careless Whisper” is the definitive recording, though. There’s no way you could actually make that record any better than it is. It’s so qualitatively good. We didn’t need anyone else to come and make the records for us. That’s no better illustrated than with the other “Careless Whisper” — the Jerry Wexler–produced version, which regrettably lost its character and personality. So the making of records was there in our nature, but it just needed the opportunity and the environment to be realized. The recording studio was right there.

Over the course of recording the first album, of course, the record company assumed we’d need a producer. We probably didn’t, really. But certainly by the time we came to record “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go,” which was the first record produced solely by Yog. The proof is in the pudding. We were left alone by the record company. We weren’t A&R’d. I’m not sure we would’ve taken very kindly to have been A&R’d, to be honest with you. The record company was hands-off and remained that way.

His voice developed as Wham!’s career evolved. The tour that we undertook in late 1983 developed his voice. There was at least a nine-month, if not a year, hiatus between the writing and recording of the new material. If you listen to the vocal performance, let’s say, of “Club Tropicana” or “Nothing Looks the Same in the Light” and then listen to “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go,” his voice had developed immensely. The tour really facilitated an environment where his vocal ability and confidence in his vocals grew. He did break down his voice because, unbeknownst at the time, he had polyps on his vocal cords, which meant that we had to reschedule dates. But you’re going to get some good practice doing the set every night for 30-odd days.

I think elements of the music press and music industry were very slow to realize his talent as a songwriter, singer, and producer. In the documentary, there’s footage where Elton John expresses bemusement with that fact. I can only assume people and the media — and even some peers of ours — were too preoccupied with the way things were presented to see beyond that, and perhaps disliked the ambition we had and the way we actually approached the business as a whole. The industry was not a sacred cow. The business of writing and making records was serious, but the business of presentation was not. Whereas it was for some people. I think people felt Wham! diminished the art in some ways. But, you know, there’s not a great deal of art in pop music. People came around to it in the end, but the tardiness with which they did so is their problem, not ours, and certainly not George’s.

I think the respect that he was afforded was, in some quarters, begrudgingly or grudgingly given. But we never made records to gain the respect of music reviewers or magazines. We made records for people to listen to. That was the primary purpose. Yog always felt that way, although I think it got under his skin a wee bit, certainly at first, the lack of acknowledgement that came his way in the early days.

Yog referenced our friendship in a couple of his songs. I love that in “Freedom! ’90” he mentions what it was quite explicitly, eloquently, and concisely. It describes our experience perfectly and two verses are given over to the subject of Wham! It’s further immortalized. I can recite it for you:

Heaven knows we sure had some fun boy

What a kick just a buddy and me

What a kick just a buddy and me

We had every big shot

Good-time band on the run boy

We were living in a fantasy

We won the race, got out of the place

We both reflected on and viewed what was a golden chapter in our lives as just that. We were aware that we achieved something extraordinary for a mutually held ambition. As teenagers, we grasped it, we realized it, and we were both aware of what we had done. We viewed it, and I still do, with great fondness — that chapter in our late adolescence when we went from boys to young men.

As we say in Blighty, just take your pick. There were several standout moments for me. The Symphonica tour was outstanding. A thing of rare beauty, in actual fact. Aside from that one, funny enough, what comes to mind was a rehearsal for his Cover to Cover tour. When I saw the show that night, he didn’t play it live, which was a bit of a shame. But I was at a rehearsal and he performed “What a Fool Believes” by the Doobie Brothers. It was breathtaking. That is an exceptionally tough vocal to match from Michael McDonald. His rendition raised the hairs on the back of my neck. It was so physically powerful and very, very few vocalists could have performed and conveyed the pathos of that song. And he did it peerlessly.

I think an example of that peerlessness would be the fact that Queen asked him to close the show for the Freddie Mercury tribute, which he did with “Somebody to Love.” That’s another song where you could count on one hand or three fingers, perhaps, the sum total of male artists who would’ve been able to adequately perform it at that point in time. I listened to it in the car. I was traveling with some friends. It was an extraordinary moment. His voice, for me, was his singular greatest talent, and the instrument by which he expressed every sinew and fiber of the songs that he wrote and songs other people wrote. His ability to physically illustrate and convey the power and meaning of songs was done with his amazing voice.

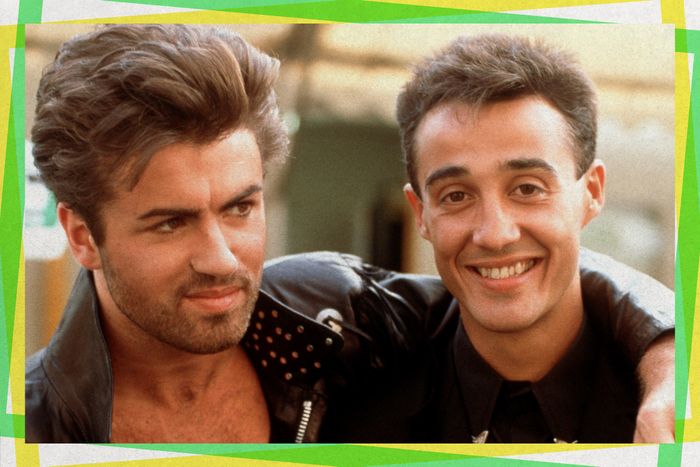

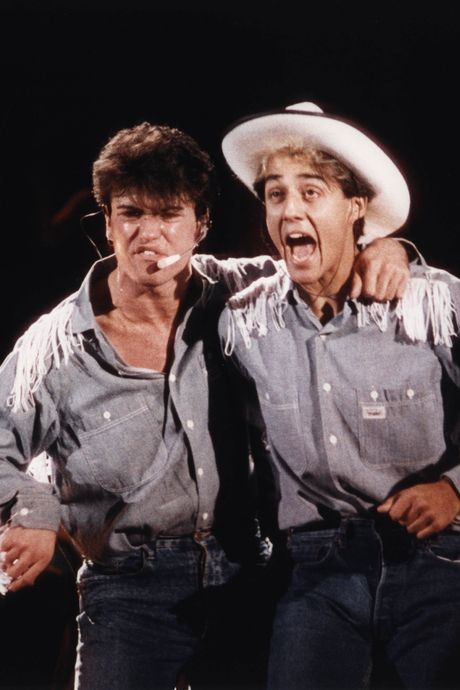

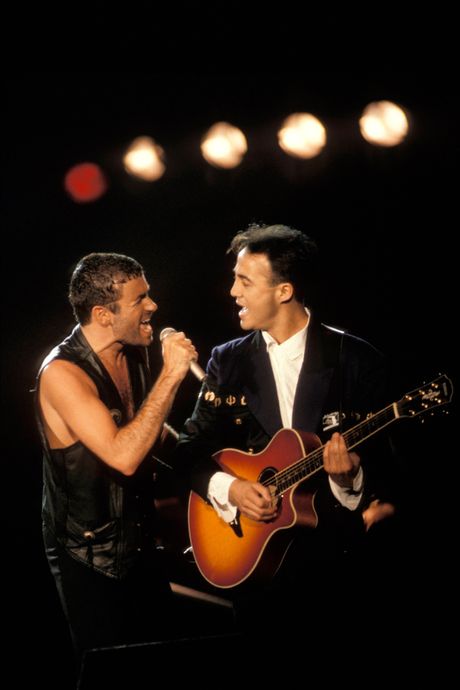

Michael and Ridgeley, performing together through the years. From left: Photo: Pete Still/RedfernsPhoto: Mick Hutson/Redferns

Michael and Ridgeley, performing together through the years. From left: Photo: Pete Still/RedfernsPhoto: Mick Hutson/Redferns

The fact is he and I did perform several times subsequently — when he toured for Faith and we performed together at Rock in Rio in 1991. But we resisted the lure of a reunion with steadfastness, because we retired and brought Wham! to a close. His artistic destiny lay beyond Wham! We understood quite early that one day the constraints that Wham! imposed upon his songwriting scope were too narrow. He wouldn’t be able to develop fully as an artist within the parameters that Wham! set. Wham! was that representation and manifestation of our youth. It was all about the vigor, experience, vitality, and exuberance of youth. We were no longer young at 23. We had become young men. If you look at photos of Yog around 1982, and he’s a wholly unremarkable and unprepossessing young chap. And then when you look at him at Wembley Stadium for our final concert in 1986, he looks God-like. The transformation was complete. He had become George Michael.

It was so much of a temporal and nonphysical representation of our youth that it just couldn’t come with us. We couldn’t drag Wham! into middle age. We couldn’t drag Wham! into performing “Young Guns (Go for It!)” at the age of 60. It wasn’t ever going to work. Obviously, the temptation was there for both of us. Not so much the money, but we enjoyed being onstage together. That’s why he invited me to perform with him every now and again. But it wasn’t as Wham! Other people saw Wham! in it but it was never in an official capacity. We wouldn’t do that to Wham! It pretty much became an unspoken rule. We discussed it one time: “We cannot reform and we can’t appear again as Wham!” Because it would’ve been a betrayal of everything Wham! stood for, really. It wasn’t to be produced in that fashion. So we never raised our heads to reunite. I don’t think we were ever really approached to do so, because people knew we wouldn’t. But who knows. Maybe they just weren’t interested.

See All

The first round of the song’s production occurred in Alabama. Michael was unhappy with Wexler’s contributions, which encouraged him to produce “Careless Whisper” himself. In a particularly Steely Dan–esque move, Michael fired several saxophonists before finding the perfect one for the solo.

The benefit concert occurred in April 1992, and also featured the likes of David Bowie, Robert Plant, and Axl Rose.

[ad_2]

Source link