[ad_1]

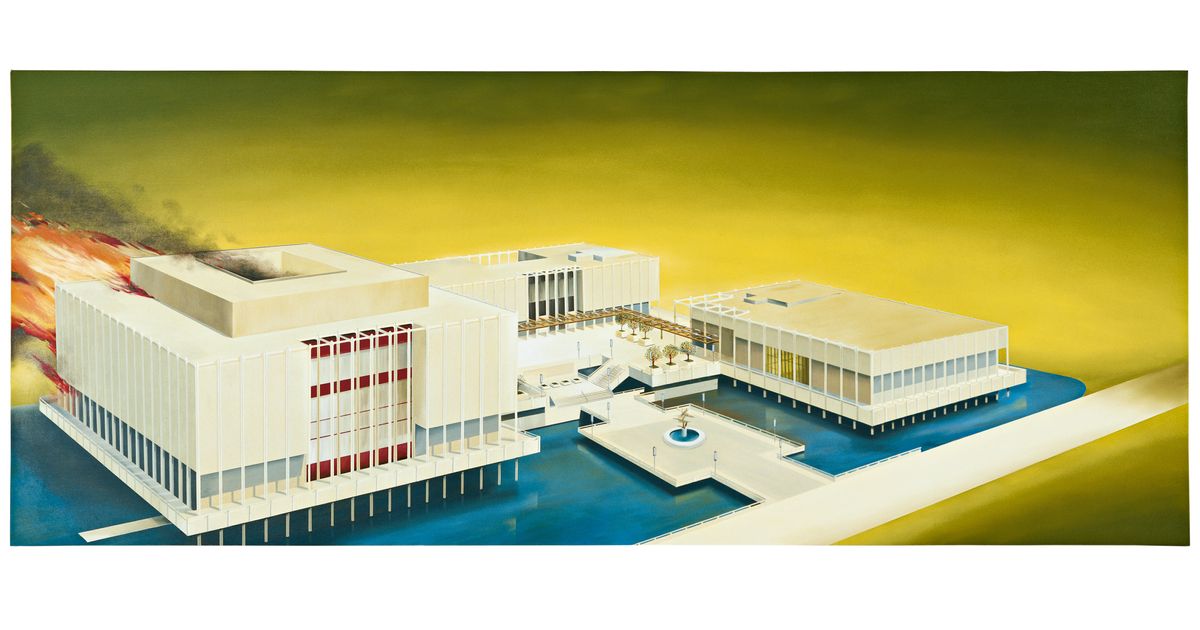

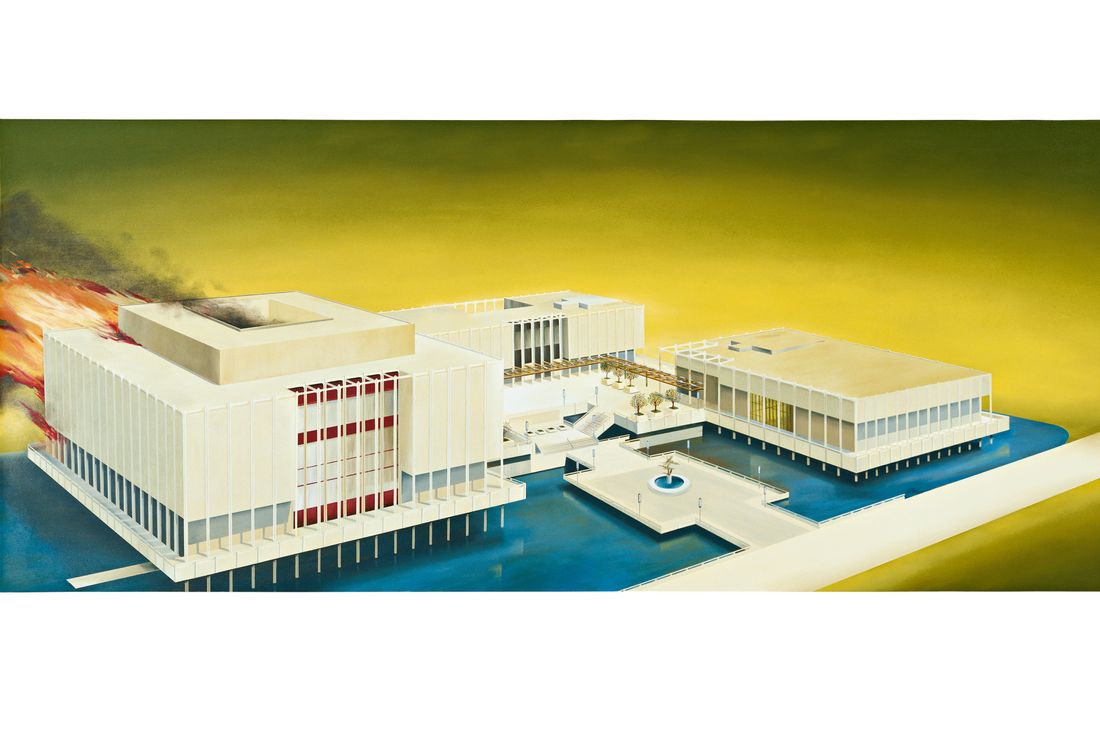

Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Fire

Art: © 2023 Ed Ruscha. Photo Paul Ruscha.

As Warhol was patron saint of the New York night, Ed Ruscha is the quintessential artist of Los Angeles and its heartbreaking light. His paintings, books, photographs, films, and works on paper — made with ingredients as disparate as gunpowder, sulfuric acid, chocolate, urine, Pepto-Bismol, tobacco, and rose petals — could only come from someone who embodies L.A.’s glamour and chaos, its self-consciousness and banal hopes. Peter Plagens once described Los Angeles as “all flesh and no soul, all buildings and no architecture, all property and no land, all electricity and no light, all billboards and nothing to say, all ideas and no principles,” a sentiment that Ruscha — 85 years old and still a dreamboat — both embraces and turns on its head.

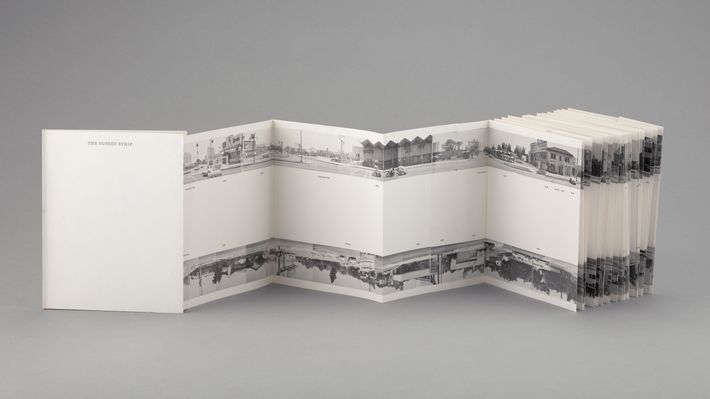

Consider three works by this multidisciplinary genius of Pop Conceptualism, now on display at “Now Then,” a career-spanning retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. One of his masterpieces, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, epitomizes Sol LeWitt’s observation that successful works of art are often “ludicrously simple.” Ruscha mounted a 35-millimeter camera with a large film cartridge on the back of a flatbed truck and drove the one and a half miles of the Sunset Strip. The transcendent result is nearly 25 feet long and seven inches high, folded like an accordion to make a book. “If there is any facet of my work that I feel was kissed by angels,” Ruscha once remarked, “I’d say it was my books.” I’ll say.

Every Building on the Sunset Strip

Art: © 2023 Ed Ruscha. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Department of Imaging Services, photo Jonathan Muzikar

Every Building on the Sunset Strip features one side of the street running like a ticker tape along the top, and the other side unspooling along the bottom, the buildings flipped so they are facing downward. It resembles a cross between a film reel, a Chinese scroll, and an ancient work of cartography, like that Borges story about the map that is at a one-to-one scale of the empire. The urge not only to know but to catalogue and record runs deep in our species. It is a form of completionism. In Every Building, we see every bit. It is both skeptical and sincere, channeling Plagens’s idea of “all buildings and no architecture” while giving the whole scene an architecture that bends on itself, housed at MoMA in a plexiglass box in the center of a large gallery.

When Warhol saw it, he reportedly remarked, “How do you get all these pictures without people in them?” I wonder that still. You feel like the only person on earth when you look at it. Ruscha said he moved from Oklahoma to L.A. at the age of 19 because he was “drawn by the most stereotypical concepts of Los Angeles,” which for him included “cars, suntans, palm trees, swimming pools, strips of celluloid with perforations.” It is a universe that is evoked here with such deadpan precision — a panorama of exteriors without interiors, a homemade prototype of Google Street views. Even the title of the piece, so deceptively simple, speaks the language of the West, where the sun sets. Strip is a wild term. It is not a street so much as it is a concentration of various commercial and aesthetic forces, a state of mind, and, in this case, a myth reddened by California light. The idea of Every Building on Lexington Avenue doesn’t cut it.

Now let’s move on to Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Fire. It was first exhibited at Irving Blum Gallery on North La Cienega Boulevard in 1968. The invitation for the show was a Western Union telegram that read: “Los Angeles fire Marshall says he will attend. See the most controversial painting to be shown in Los Angeles in our time.” The movie-marquee provocation — sensational, ridiculous, exciting — is what we used to call show business. The image itself is 11 feet long, a surreal overhead view of what was then a recently constructed institution. Whereas the real-life LACMA now has qualities of both the city and the desert — a forest of lampposts out front, a megalithic boulder out back — Ruscha turns it into an island complex, the white buildings moated by water and further surrounded by gradient shades of green and yellow, all of it seemingly nowhere at all. A fire rages in the main building, its flames licking the edge of the painting.

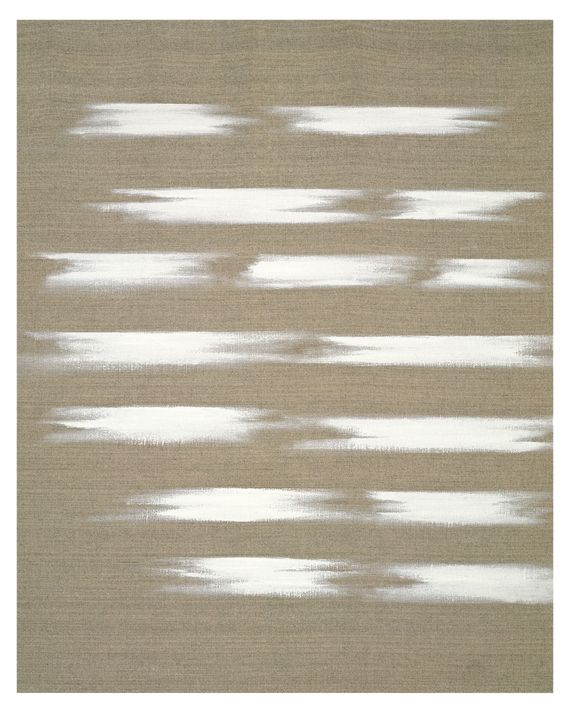

I’ll Be Getting Out Soon and I Haven’t Forgotten Your Testimony Put Me in Here

Art: © 2023 Ed Ruscha. Photo Paul Ruscha.

Even though there had been riots in Los Angeles by then, this doesn’t feel like the message. Nor is any beef Ruscha might have had with the museum. He once remarked, perhaps a little slyly, “I didn’t dislike the art museum … I had no grudges.” He went on to say that he “liked the idea of painting architecture” and that “there’s no great message here. It’s just a picture to look at.” This sort of denial of intent is typical of a whole generation of artists who created loaded images and objects, then claimed a totally formal read of the work. It is also a feint that, in Ruscha’s case, is of a piece with his vision of Los Angeles, a beautiful dream obscuring some pressing reality.

Finally, there are Ruscha’s “word paintings.” Like his I Don’t Want No Retro Spective, which is hauled out for every one of his retrospectives, including the one at MoMA. My favorites of these, however, are from the 1990s and have no words in them at all. They depict real ransom notes with the words scrubbed out, though the titles give a sense of their meaning: For example, I’ll Be Getting Out Soon and I Haven’t Forgotten Your Testimony Put Me in Here (1994), Do As I Say (1997), and Note We Have Already Got Rid of Several Like You — One Was Found in River Just Recently (1996). Each is playful, sinister, a strange reflection of our own times. The keen observations and careful execution of these paintings speak to a maniacal tendency in America toward anger, billboards that are empty of sentences but have plenty to say.

[ad_2]

Source link