[ad_1]

Photo: Michele K. Short/HBO

We’re two weeks into season four of True Detective: Night Country, and if you’re anything like me, this show is already sending you down internet rabbit holes. Like, I’m out here investigating vague allusions and spooky imagery by rewatching old episodes of True Detective, reading James Joyce, and trying to figure out if that one-eyed polar bear spotted by trooper Evangeline Navarro could somehow be connected to the Dharma Initiative. (What? It’s a legitimate and valid question that someone needs to be asking, and that someone is me.)

In this column, we will obsessively try to make sense of which elements in Night Country are just fun (but also terrifying!) little Easter eggs and which might explain the entire universe. This week’s “Part 2” provides plenty of fodder for consideration, including more information about the deceased scientists who have since turned into what Chief Liz Danvers refers to as a “corpsesicle”; the backstory behind Arctic ghost Travis Cohle (that would be Rust Cohle’s dad); and the reemergence of everyone’s favorite devil sign, the spiral symbol that first appeared in the True Detective universe back in season one. Time may be a flat circle, but it also waits for no one, so let’s get into it.

Photo: HBO/Max

The first sign that there’s something unusual about this place — aside from the fact that it’s in the middle of nowhere and seems designed to convince employees they got trapped in John Carpenter’s remake of The Thing — is its name. Tsalal does not appear to be an acronym for anything, so what does it mean? There is a Hebrew word, tsalal, that translates as “to be or grow dark,” a description that’s certainly evocative of the multiple days of night Ennis is experiencing as well as the purportedly black water coming out of some residents’ faucets. But the word also appears in literature as the name of an Antarctic island in Edgar Allan Poe’s novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket and a subsequent sequel of sorts, An Antarctic Mystery, which was written by Jules Verne.

Contemporary horror writer Thomas Ligotti borrowed the word from Poe for a story called The Tsalal, about a forbidden text whose dark imagery and philosophy takes over the mind of anyone who reads it. The novella is difficult to find in print, though there is an audiobook version on YouTube. According to this 2010 essay on Ligotti’s work, when Andrew, the son of a fundamentalist Christian pastor, reads the Tsalal within The Tsalal, he absorbs the message that “there is no nature to things … there is no salvation of any being because no beings exist as such, nothing exists to be saved — everything, everyone exists only to be drawn into the slow and endless swirling of mutation that we may see every second of our lives if we simply gaze through the eyes of the Tsalal.”

Those words echo one of Matthew McConaughey’s first philosophical ruminations in season one, when Rust tells his detective partner, Marty (Woody Harrelson), that humans are “creatures that should not exist by natural law. We are things that labor under the delusion of having a self, this accretion of sensory experience and feeling, programmed with total assurance that we are each somebody. When in fact, everybody’s nobody.” Is it possible that the scientists gazed through the eyes of Night Country’s equivalent of The Tsalal and had a similar, disturbing realization?

We learn some other facts about the scientists courtesy of Adam Bryce, the high-school science teacher who is also on Liz’s apparently long list of local sexual conquests. He says the men have been trying to sequence the DNA of an extinct microorganism, an effort that could stop cellular decay and lead to cures for cancer and genetic diseases. In other words, these guys have been trying to figure out how to prolong human life. Bryce also notes in passing that the scientists have been at Tsalal for decades and never rotated crews, a common practice at other Arctic centers. If we take Bryce at his literal word, this suggests that everyone on the Tsalal team has been living there for at least 20 years, even though at least one or two of them look too young to have been there for that long. What if the scientists had already been attempting to stop their own cellular decay — and succeeding?

Bryce is adamant that their efforts were destined to fail: “Permafrost is hard and it damages chromosomal material on extraction, so it was never gonna work,” he explains. But what if global warming has softened some of that permafrost and it actually was working? Could someone or something have wanted to stop their progress in order to restore “natural law”?

One more important thing about Tsalal: Prior (Finn Bennett) tells Danvers that an NGO pays the center’s taxes, but the money can be traced back to a shell company owned by Tuttle United, a corporation that, according to Prior, does everything: “glass, tech, video games, shipments, palm oil, cruise lines.” What is this, Waystar Royco? Entertainment 720? No, based on the name, it sounds like a front for the cult run by Louisiana’s Tuttle family in season one of True Detective, a cult responsible for the abuse and deaths of many children. Danvers blows off Prior’s research, saying, “Thanks, Petey. That was really unhelpful.” I don’t know, Liz, sounds pretty meaningful to me.

Do all these Tsalal clues add up to a real theory, or are they just eerie?

They are definitely eerie, but there’s enough established connective tissue between what’s happening now and the preestablished mythology in True Detective to potentially add up to something. All the President’s Men taught us all to follow the money, and what Prior has found suggests it’s worth continuing to follow.

Photo: HBO/Max

If you’ve watched previous seasons of True Detective, all the hairs on the back of your neck probably stood up when this symbol made a reappearance in Night Country. For those whose memories of the spiral are a little fuzzy: This iconography played a major role in season one, appearing first on Dora Lange, a 1995 victim of the so-called Yellow King killer, and functioning as a marker of those connected to the Tuttles’ twisted religious, pedophile cult.

In Night Country, the same swirling symbol is etched on the forehead of one of the scientists, while another Tsalal resident, the missing Raymond Clark, got a tattoo of it. So did Annie K, the Indigenous woman whose disappearance/likely murder continues to nag at Navarro’s conscience and who appears to have been in a romantic relationship with Clark. The spiral marking is also found on the ceiling of the camper that Clark apparently bought from miner Chuck Mosley. (By the way, did you notice the dolls hanging in that trailer that looked a lot like the cornhusk dolls from season three?)

From all of this, can we infer Clark is, at best, creepy — I lost count of how many times people said the dude was weird in this episode — and, at worst, responsible for Annie’s death? Showrunner Issa López seems to be hinting at that based on nomenclature; as has been noted in Vanity Fair and elsewhere online, Raymond Clark also happens to be the name of a Yale lab tech who pleaded guilty in 2011 to the murder of a graduate student whose name was … Annie Le.

That said, we don’t have enough info about the symbol in a Night Country context to say whether it definitely connects to the same cult we’ve seen on this series before. There is a chance it could simply be a callback to previous seasons and that the symbol has its own, separate meaning in Alaska. When Navarro asks Rose (Fiona Shaw) about the spiral, Rose says it is “older than Ennis” and probably “older than the ice.” This suggests the spiral could be more reflective of Indigenous symbols from this part of the earth, going back for centuries. Indeed, spiral imagery dates back to cave etchings and rock drawings from thousands and thousands of years ago. As noted by the Bradshaw Foundation, a nonprofit focused on archaeology and anthropology, the circular symbol became very prevalent in the Americas, often in sites “thought to be associated with cultural use of hallucinogenic drugs or rituals.” It’s very possible the freaks in Louisiana were appropriating it and assigning it their own meaning. Still: kind of a weird coincidence.

Does the presence of the symbol add up to a theory, or is it just eerie?

It feels meaningful, especially given all the other nods to the Yellow King and previous True Detective seasons. But at this stage, it’s hard to say what that meaning is.

Photo: HBO/Max

There are a lot of references to eyes and sight in the first couple of episodes. At the beginning of “Part 2,” Prior notes that one of the dead scientists appears to have scratched out his own eyes before he died. The polar bears — both the one Navarro spots on the road in the previous episode and the stuffed one that belonged to Danvers’s son — have one eye missing, as if it also was scratched out. The drawings Navarro and Danvers discover in Clark’s trailer feature several allusions to eyes, including images that look like pairs of eyes peering out from scribbles resembling tornados and the words “her eyes, her face” written repeatedly.

Once again, all of this echoes previous True Detective eras, including season one, and the mirror in Rust’s apartment that Marty joked was only large enough to reflect one eye; season two, when sexual deviant Ben Caspere’s eyes were burned out with acid; and season three, when Junius Watts, a character with only one eye, played a crucial role in what happened to Julie Sullivan, who went missing in 1980. In season four — and some of the previous examples too — impaired vision seems to goes hand in hand with witnessing something alarming and possibly revelatory. One of the Tsalal scientists seemingly scratched out his own eyes after witnessing something that perhaps gets at the truth of what’s happening in Ennis, while the polar bears function as some sort of key that unlocks memories or insights for Danvers and Navarro.

If we again look to symbols from ancient history, there are examples of missing eyes in meaningful contexts that perhaps shed some light on what Night Country is doing with all this. Consider the Aztec god Xolotl, the god of death, who lost his eyes after failing to sacrifice a part of himself to the sun. Maybe all this stuff about eyes that don’t fully function is just another way to highlight how hard it is to see clearly, literally and figuratively, during those long days of darkness.

Do the eye references add up to a theory, or are they just eerie? They are eerie and potentially symbolic. But they don’t explain anything, at least not yet.

Photo: HBO/Max

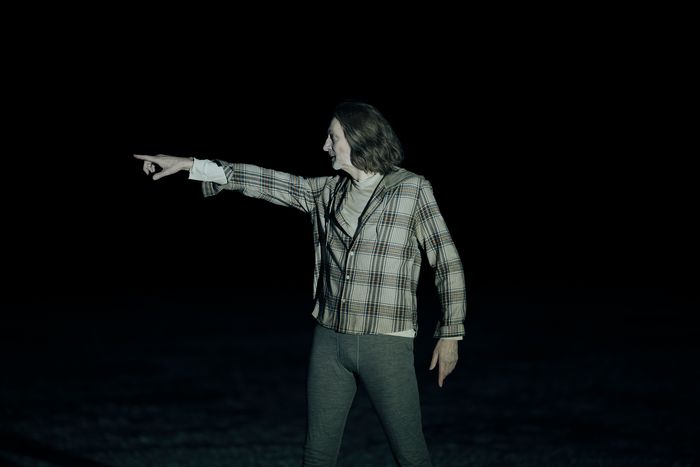

During the scene where Rose tells the story of how Travis — the father of Rust Cohle — died, Tim Buckley’s “Song to the Siren” plays on the soundtrack. That track alludes to the story of Odysseus, who must resist the temptation of the sirens’ beautiful music, which is known to persuade men to kill themselves.

As Rose recounts what happened to Travis, she describes how he took his own life rather than wait until he succumbed to leukemia, information that confirms that Rust’s dad, who lived in Alaska, really was dying as Rust once claimed. But did he plan to take his own life? Or did he fall victim to a siren song and become convinced to throw himself below the ice? Is it possible that a similar temptation took hold of the scientists as well, persuading them to run outside naked in frigid weather?

It’s perhaps also worth noting that in another Odyssean tale, James Joyce’s Ulysses, the father of the protagonist also takes his own life. He does so in a hotel … in the town of Ennis, Ireland.

Is Travis’s backstory grounds for a theory, or just eerie? I think there is something in Travis’s story that may help explain what is happening in Ennis and how that affected Annie K and the dead men of Tsalal. It’s worth holding in the back of your mind during future episodes.

Photo: HBO/Max

This episode explains why Liz was so agitated when she couldn’t get the parade scene from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off to stop playing at the Tsalal station. The song “Twist and Shout” triggers her not because she dislikes the Beatles — though if anyone were to dislike the Beatles, Liz seems the type — but because it reminds her of her baby, whom she once sang the song to, as we witness in a flashback. (Also, to go back to the eyes for a second: While playing with Liz, the kid covers one of his eyes and says, “I’m the one eye,” most likely a reference to his stuffed polar bear. Which is kind of freaky.)

That scene functions as a complement to the moment when Navarro hears “Wannabe” by the Spice Girls and is immediately reminded of similarly happy times with Julia, her baby sister. The music choices here — and by the way, all of them in this episode are so good, right down to corpsesicle arriving at the ice rink to the tune of the Beach Boys’ cheery “Little Saint Nick” — underline the generational divide between Danvers and Navarro. Liz, a boomer, introduces a younger generation to the Beatles; Evangeline, a millennial, goes with the Spice Girls. But both women find joy and connection through music, a sign that there are similarities between them despite their divisions.

I found myself wondering, though, why the Tsalal guys would have Ferris Bueller’s Day Off in their regular movie-watching rotation, aside from the obvious reasons: It’s funny and some of them probably grew up watching it. I concluded that within the narrative, the film helps underline the injustice of Annie K’s case. This is a John Hughes movie about a kid who takes a sick day — in his upper-class, suburban-Chicago, 1980s way, he goes “missing” — and whose absence is so immediately felt that some of his classmates start a fundraiser and Wrigley Field posts a “Save Ferris” PSA in his honor. That stands in sharp contrast to the case of Annie K, an Indigenous woman in present-day remote Alaska whose disappearance didn’t raise nearly enough eyebrows.

Life moves pretty fast. If no one stops and looks around for you, you could just be forgotten.

Does the Ferris Bueller allusion add up to theory, or is it just eerie? Honestly, it’s neither. It’s just an interesting use of irony that maybe I am reading too much into, if it’s possible to read too much into anything on True Detective: Night Country.

See All

[ad_2]

Source link