[ad_1]

This article was originally published on August 29, 2023. We are recirculating it now that Killers of the Flower Moon is available to stream at home. Be sure to also read our review, share in our admiration of Martin Scorsese’s press stamina, and see what Nate Jones thinks about the movie’s Oscar chances.

Before she was cast as the anguished center of Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, before she played a grief-stricken mother on Reservation Dogs, and before her breakout role in Kelly Reichardt’s Certain Women, Lily Gladstone taught school children about Native American history. She taught while in character as part of an educational theater program — the kind of steady work you’d feel lucky to get as a young actor (which Gladstone was at the time), even if it wasn’t what you dreamed of doing as an acting student (which she had been at the University of Montana not long before) — touring alone to school auditoriums, trading lines with a prerecorded track about having to shed her culture while a multimedia presentation was projected behind her. She played Alice, a Navajo girl who endured an abusive, assimilationist education in order to become a nurse. The part didn’t reflect Gladstone’s background — her father is Blackfeet and Nez Perce, her mother white, and her childhood was split between Montana’s Blackfeet Reservation and Seattle — but it wasn’t entirely distant, either. Her grandmother had attended one of those infamous boarding schools, Chemawa, from which hundreds of children never returned; they are buried there in marked and unmarked graves.

It was rewarding for Gladstone to expose young audiences to facts that weren’t included in their textbooks, even if she had to supplement the job with weekly shifts at Staples for health insurance. But serving as an envoy for the injustices and suppressed stories of a whole people was exhausting. “It makes you tough,” she told me in New York in June before the start of the SAG strike. By her last performance, a month after she had finished filming Certain Women, “there was nothing more I had to give to it. If I were to do that kind of work again, that history about trauma to our communities, I would want to do it with the community, not alone.” With Killers of the Flower Moon, it seems, she has found a way.

Onscreen, Gladstone is known for her silences — for being an observer and for her singular ability to hold a viewer’s attention without needing to speak. “She had a very sharp sense of her own presence before the camera and an extremely unusual trust in simplicity,” observes Scorsese, who chose her to play Mollie Burkhart, an Osage woman living in 1920s Oklahoma and the female lead of the film. “That’s a rare thing. You can’t take your eyes off her.” She got her first movie role, in a 2013 indie called Winter in the Blood, after serving as a reader during an open call in Missoula. Gladstone had acted in one of the directors’ student films and wasn’t actually auditioning, just helping out. But casting director Rene Haynes found her attention drifting in Gladstone’s direction throughout the day: “She wasn’t stealing the spotlight or anything like that. But she was just so riveting.”

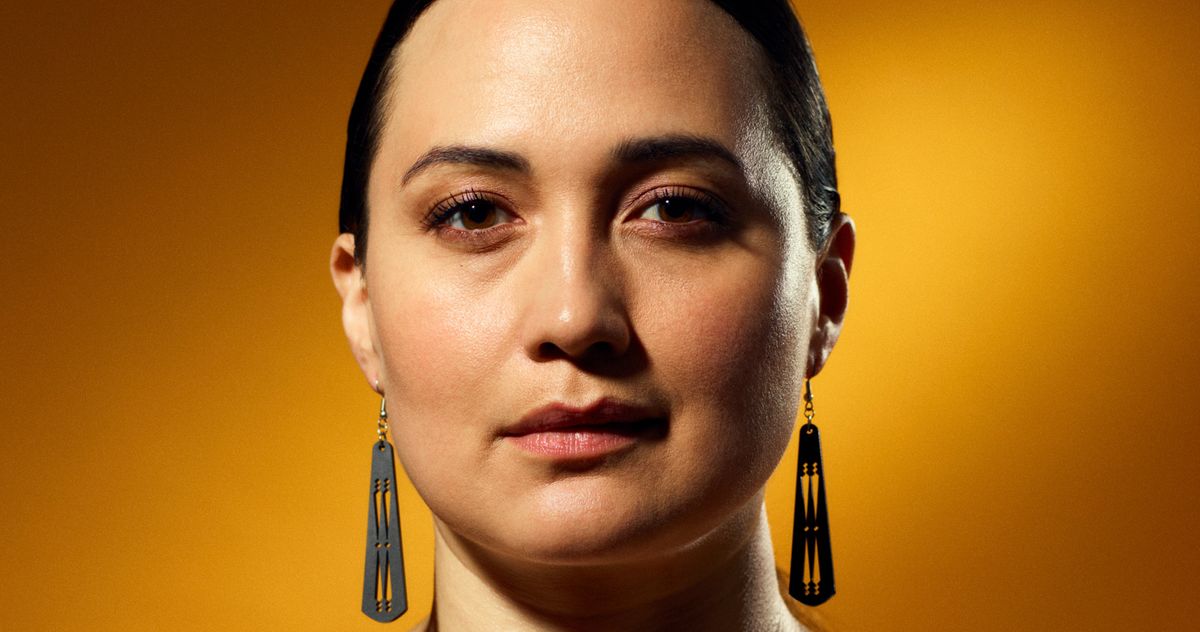

Despite having such a prized quality in her performances, Gladstone has never thought of herself as especially quiet. “I’m a character actress. I was always the squirrelly, overcharged kid,” she reflects with a deliberation that seems characteristic. In person, she’s earnest but can be disarmingly chatty, sharing childhood family photos and behind-the-scenes videos from set on her phone and telling stories about how her father loved that Scorsese had palled around with the Band’s Robbie Robertson. (“You got Hollywood’s greatest director just hanging out with the Indians!”) It’s her face, she thinks; that’s the reason — and it is a very good face with the oval symmetry of a Madonna statue and an emotional clarity that makes you feel as if you can see her thoughts. “My dad, when I was little, always told me I couldn’t lie to him because you could see what my face was doing,” she says. She also credits the time she has spent in the company of elders: “I got used to being in a position where you’re open and ready to learn and listen. Somebody who is listening is super-interested. I think that’s what’s interesting toa camera, but who knows?”

Photo: Hugo Yu

Gladstone is 37 now, and her performance as Mollie has been the most buzzed-about part of the movie since it premiered at Cannes and kicked off a seemingly inexorable march toward awards glory, slated to reach theaters on October 20. But back in 2019, when she was first approached for the role by casting director Ellen Lewis, the project looked very different. The film, which Dune screenwriter Eric Roth adapted from David Grann’s 2017 book, takes place a few decades after oil was discovered on the Osage Nation Reservation, when the money from that boom brought enormous wealth to the community along with a rush of attention from opportunistic outsiders who tried to get a piece of it through marriage, manipulation, or murder. Leonardo DiCaprio, who eventually took on the role of Mollie’s slippery husband, Ernest, was initially set to play Tom White, the proto-FBI agent who leads an investigation into the ongoing killings of the Osage, crimes the local police were indifferent to or in on.

Gladstone had planned to accept the part if it were given to her — “You don’t say no to that offer” — but she was nervous about this brutal chapter in Osage history being framed as a mystery to be solved by swashbuckling federal law enforcement. Mollie’s family were among those targeted for their headrights — lucrative shares of the mineral royalties, which were passed down through families and which you didn’t have to be Osage to inherit — but Mollie’s sisters (played by Cara Jade Myers, Jillian Dion, and Janae Collins) didn’t seem like significant presences in the script. Then the pandemic and what Gladstone refers to as “the great rewrite” happened, reportedly at DiCaprio and Scorsese’s urging. Rather than focus on White (who does show up late in the film, played by Jesse Plemons), the new version centered on the Osage and the structures that allowed others to get away with brazenly killing them.

“It’s not a white-savior story,” Gladstone says of the film they ended up making. “It’s the Osage saying, ‘Do something. Here’s money. Come help us.’” It’s clear from the start that William Hale (Robert De Niro), a prominent local landowner and self-proclaimed friend to the Osage, is conspiring to accrue all the oil rights he can and that Ernest, his nephew, obeys his orders, including a strong suggestion to romance and wed Mollie for the windfall it could bring; Ernest eventually comes to love Mollie even as he helps bring about the deaths of her friends and family. The Burkharts’ disturbing marriage became the core of the film, an intimate version of the predation happening to the local Native community as a whole. The relationship reminded Gladstone of the love triangle in Graham Greene’s novel The Quiet American, in which the dynamics between a British journalist, an American CIA agent, and a Vietnamese woman come to represent the West’s intrusions into Vietnam.

Just as important to Gladstone was that the Indigenous community in Gray Horse, Oklahoma, where some of the killings took place, had invited Scorsese to a dinner in late 2019, which he attended. She saw it as a sign that the Osage intended to be heard in the production and that Scorsese wanted to hear from them. And from her: “It was clear that I wasn’t just going to be given space to collaborate. I was expected to bring a lot to the table.” In particular, she saw similarities between Mollie and her own great-grandmother, both devout Catholics who were also deep adherents of their Indigenous cultural traditions. “That gave Marty and I a lot to talk about,” she says. “That’s what being equitable is — not just opening the door. It’s pulling a seat out next to you at the table.” As a non-Osage actor starring in a story about such a bleak stretch of Osage history, she wanted to involve herself with the community as much as it would allow. The Osage person she now counts as her “best friend in the world” initially kept Gladstone at arm’s length. Now, when she goes back to Oklahoma to visit friends and to attend the private annual Grayhorse Inlonshka dance, it’s like a reunion.

DiCaprio and Gladstone as husband and wife.

Photo: Courtesy of Paramount

Gladstone has thought a lot about the stories that get told about Indigenous characters and who gets to tell them: “There’s that double-edged sword. You want to have more Natives writing Native stories; you also want the masters to pay attention to what’s going on. American history is not history without Native history.” To have someone on the level of Scorsese make a film about the Osage murders means attention and scale. At the same time, she’s aware of filmmakers in the past who have parachuted into tribal communities only to leave the members regretful for participating in their projects.

Being a working actor means not always having the liberty to pick and choose your material, especially when those pickings are slim. Over the years, Gladstone has appeared in work by Native and non-Native artists alike. She’ll happily dunk on the cowboy mythmaking of Taylor Sheridan (“Delusional! Deplorable!”) but adds of Yellowstone, “No offense to the Native talent in that. I auditioned several times. That’s what we had.” Even during those lulls, she had a way of lingering in the minds of those who had seen her work. A few years after casting her in Winter in the Blood, Haynes was shopping at Costco when she got a call from Mark Bennett, who was trying to fill a key role in Certain Women. As a cashier rang up her groceries, she thought of Gladstone, who went on to give a performance in the film that exudes longing and loneliness in every beat. Haynes, who was also involved in casting Killers of the Flower Moon, says she will read a script and start to hear the voice of the actor she thinks could play the role. For Mollie, “from the outset, this was Lily.”

During the pandemic, Gladstone was living north of Seattle with her parents, uncle, and grandmother, whom Gladstone helped care for as she coped with dementia. (She passed away last summer; when Gladstone asked about her time in the boarding school, she said only that “there were parts of that school that were pretty rough.”) While she was in a house full of elderly and immunocompromised people, and with so many productions — including Killers of the Flower Moon — slowed or stopped entirely, work seemed impossible as she had known it when alternating jobs in theater and indie films. She had always loved bees, and after watching a video of Asian giant hornets annihilating a hive (“Not another murderous colonizer taking out the only thing that’s good and pure that’s left!”), she looked into a seasonal data-analytics job tracking the invasive species for the Washington State Department of Agriculture. Then she got the notification requesting a Zoom with Scorsese.

Now, with her name on the lips of every Oscar pundit (she would be the first Native American woman to win Best Actress), Gladstone is in the rare position of being able not just to find work but maybe even to make things happen. And there are a lot of things she’d like to make happen: a movie about jazz singer Mildred Bailey, who grew up on the Coeur d’Alene Reservation and became known as the Queen of Swing, or one about folk musician Karen Dalton, Cherokee on her father’s side, who was a favorite of Bob Dylan’s but didn’t make it big in her lifetime. There are so many stories that haven’t been told onscreen, and Gladstone now has a sense of how to figure out whom she wants to work with. It comes down to one thing, she says: “How well they listen.”

See All

[ad_2]

Source link