[ad_1]

Photo: Anthony Barboza/Getty Images

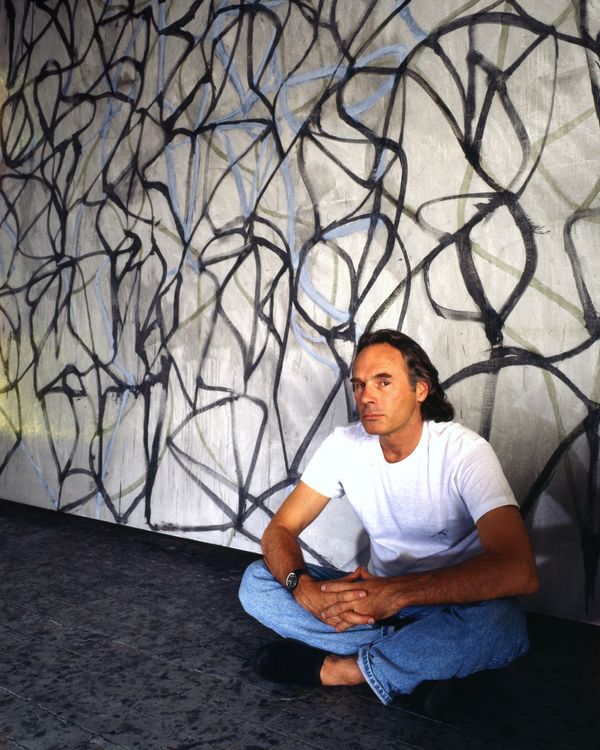

Brice Marden, who died this week at the age of 84, was a beautiful man who made beautiful paintings. They began as rich, opaque, monochromatic fields laced with highlights, flickers, nuances of gesture, little drips at the bottom of the canvas. These fields of color seemed to float, minimalism liberated into something more erotic, sensual, erratic, and rhetorical. They became what was then called post-minimalism.

He started as an assistant to Robert Rauschenberg. His early work was almost immediately well received, sold, and written about. (Strangely, his work was much slower to catch on in Europe.) Unlike many of the first-generation minimalists, though, Marden’s work never stood still. Imagine a film of all of his paintings looped together, one after the other: the early monochromes becoming more complicated, like veined marble tablets, then the introduction of those swooping, curling, overlapping lines for which he is now famous. Together, I fancy these works might spell out something mysterious and gigantic — a structure of beauty.

He was married to Helen Marden. They made for an alluring couple. Their downtown home was a menagerie of exotic objects, shabbily furnished with couches, broken lamps, and plants that grew through the front window. Imagine them sitting around, drinking and smoking at a table that saw a constant influx of visitors, including Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol. I do not think that I ever saw Brice Marden without a hat.

His late work lulls us into a hypnotic state. Think of these pieces as snakes in a box. He is so aware of the painting’s four sides, and this in fact is what his work is about: the making, the conditions in this charged field, the immense possibilities in this contained surface. He starts with a subtle monochromatic plane. On this he applies lines, usually half an inch or so thick. These ribbons of color have body and surface tension, and are spontaneous but endlessly labored for. You see under-painting — lines that were here, then gone, then might have moved over slightly. You feel the development, the unfolding, the resolution of this painting. The aura is pearl-like, burnished, imperfectly perfect.

He invented these superlong painting brushes and even painted with sticks. You are always aware of his hand moving, thinking, erasing, trying again. The lines spiral inward, change direction, move back to one of the borders, gracing it for several inches, caressing it, before curling back across the canvas. They are convection currents, thermal forces, a central nervous system, the ganglia of some strange organism remembering itself.

He once described the painting’s edges as “the infinitesimal hinge between.” That’s what Marden’s work is.

[ad_2]

Source link