[ad_1]

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Matthew Liefheit, Lawrence Sumulong

Twelfth Night, January 6, traditionally marks the end of the festive season. Unless you’re a theater person in New York City — in which case, when the New Year rolls around and brings festival month with it, you strap on your trekking boots and trade the wassail for espresso. (Or, if you’re me, really shocking amounts of Darjeeling.) With the gloriously defiant return of Under the Radar — dropped by the Public Theater, now a collaboratively produced endeavor partnering with multiple companies and venues all over the city — there’s much to celebrate. Overcome with completionist ambition and/or madness, I’ve decided to try to catch every show UTR is producing this year, along with as many as I can from its fellow festivals, all eccentric, all exciting. There’s Prototype, NYC’s annual celebration of radical contemporary opera and music-theater; the Exponential Festival, a jamboree of emerging, experimental work based in Brooklyn; and, for the first time, PhysFestNYC, in case you find yourself in Fidi and think, I could really go for some mime right now.

Instead of filing conventional reviews, I’m keeping a weekly public diary this month with a wrap-up at the end. I may not write about everything I see; many (perhaps most) of these productions in development, and if the makers want me to hold off at this point, I will. For those that are ready, I’ll be sharing my personal highlights and, most of all, encouraging you to come out. It’s been a long, cold winter for theater, and it’s hardly over — all the more reason to raise a glass to January’s spirit of abundance.

They’re promising snow tonight, and, oh yeah, the 1 train is effed, so it’s a walk from Columbus Circle and a snack along the way. (Reviewing theater — like making it — means a lot of 11:30 p.m. dinners.) I’m seeing three shows back-to-back upstairs in the rehearsal studios at Lincoln Center Theater: Search Party by the Nigerian poet/playwright/performer Inua Ellams; The First Bad Man by Pan Pan Theatre; and Queens of Sheba, a choreopoem by Jessica L. Hagan and Ryan Calais Cameron. It’s international night: Ellams lives in London, Pan Pan is in Dublin, and the artists behind Queens are mostly London-based (Hagan splits time between London and Ghana).

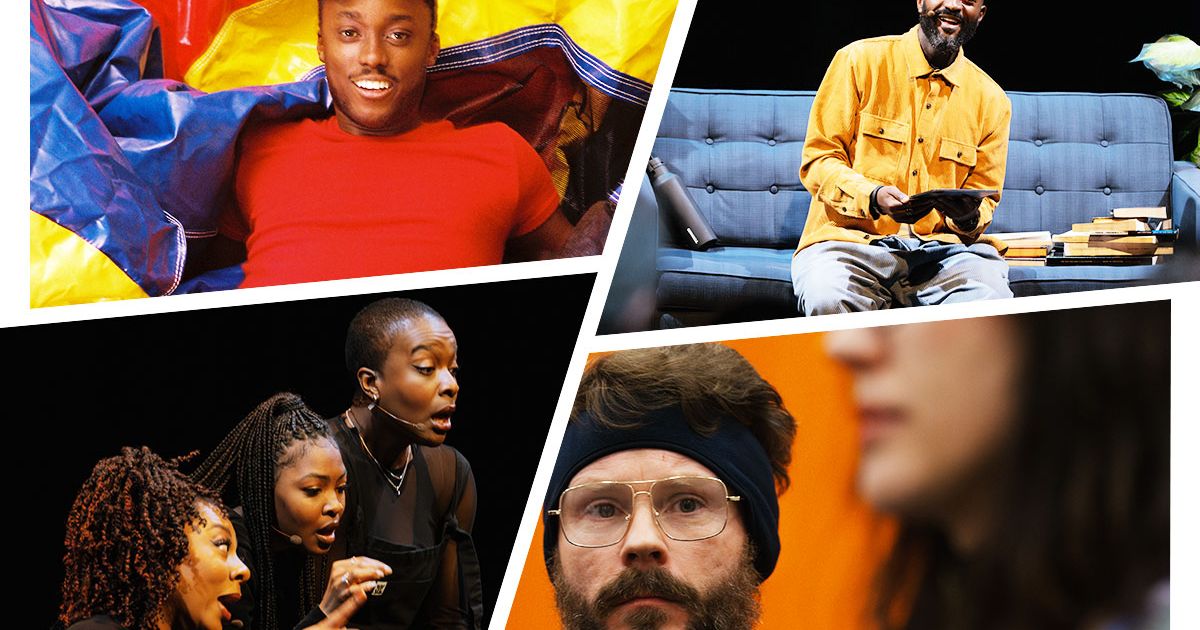

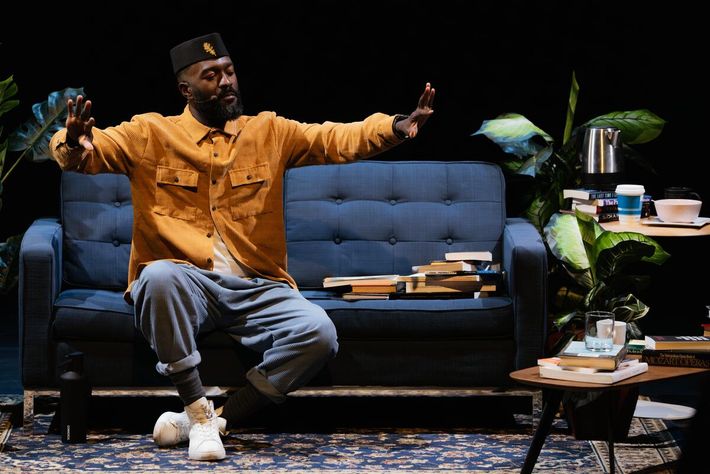

None of the shows is more than an hour long. It’s exciting to get into the quick-and-dirty festival mindset — set it up, do the show, throw it all back in the road case, and clear out to the bar, all in under 90 minutes. Ellams, who, as the evening starts, wanders casually into the theater space — set up cozily for him with a couch, a standing lamp, piles of books, houseplants, a teapot — is gentle and charming. He gives the impression of being a curious audience member at his own show. This is all going to be simple, he tells us: We, the audience, will shout out words, he’ll enter them into the search bar of his iPad, and he’ll read us the result — whatever poem or essay or bit of text they call up from his archive. Together, we’ll all have a Search Party.

From Search Party.

Photo: Lawrence Sumulong

Ellams’s welcoming, soft-spoken, ultra-casual manner could fool you into thinking this is his always-vibe — but Search Party is clearly the work of an immensely erudite, multifaceted, and busy artist working in an intentionally flexible, low-key mode. Ellams is a poet and a playwright (NYTW presented his Half-God of Rainfall last summer, and during a Q&A portion of his show, he lets on that he’s working on an epic drama about pre-colonial Nigeria, matriarchy in ancient Islam, and the Trans-Saharan slave trade). He’s also a performer, a screenwriter, a graphic artist, and a designer (the man’s even got an MBE). And — despite a childhood, he tells us, that was mostly musically influenced by his father’s taste for Kenny G and his mother’s for gospel — he’s a late-blooming lover and self-made scholar of hip-hop. His poetry is thoughtful, tender, and muscular, but the high point of our particular search party is undoubtedly a “14-minute long essay on Tupac” that he somewhat hesitantly asks our permission to read. It’s an exegesis of his poem “Fuck / Tupac.” He’s apparently gotten some flack for the title, but the poem itself — and the essay it sits within — is an elegy, a sincere gift, a real act of love.

Search Party won’t ever be the same from performance to performance. Nor will Pan Pan’s surreally tilted take on Miranda July’s novel The First Bad Man, which, although it certainly plays out along a structure, has the static-electricity tingle of partial improvisation. It feels heightened and risky, a little loopy and a little tense — like trying to keep a ball in the air, or not stepping on certain bits of the floor because they’re lava.

From The First Bad Man.

Photo: Lawrence Sumulong

We’re all handed paperback copies of July’s book upon entering the performance space. The premise is that we’ve been invited to a book club. I’m a little unclear whether or not the Pan Pan folks actually expect us to have read any (all?) of the book, but whatever — plenty of book-club participants don’t do the reading anyway. I’m early, so I get about 30 pages in. That’s useful — I now know who “Cheryl,” “Phillip,” and “Clee” are, which will help over the next 60 minutes.

Mostly in full bright light, with the audience spread around in the room in individual chairs that all face centerward, the show’s four performers alternate between discussing the novel, reenacting it, and slipping into surreal musical interludes that set bits of its text to glitchy, throbby ambient music. I found myself thinking of Charlie Kaufman and — when the reenactment begins — of Anne Washburn’s Mr. Burns. The brilliant gambit of that show is to watch a bunch of apocalypse survivors attempt to act out, from memory, episodes of The Simpsons (in the framing of the play, a revered artifact long since lost to time). As Pan Pan’s actors, deadpan and stiff-limbed, paraphrased their way through July’s story, I could feel similar vibrations — the buzz of weird, stunted souls and awkward bodies groping for some form of communal expression and connection, no matter how embarrassing. Which, basically, is theater.

Queens of Sheba is also an intimate collaboration by four performers: On an empty stage, dressed in black, Paisley Billings, Déja J. Bowens, Jadesola Odunjo, and Muki Zubis dance and sing us through an exploration of misogynoir. “They ask me where I am from!” goes one of the show’s refrains, “I say I am a mix. Of both racism and sexism — they lay equally on my skin. Passed down unknowingly by my next of kin.” Queens is a conscious descendent of Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, and like that choreopoem (Shange herself coined the term), it blends dance, movement, rhythmic speech and repetition, and sung harmonies to explore its painful, personal subject matter. In the face of that pain, the performers work and play to hold each other up — they keep laughter, celebration, and satire in the room, passing the sustaining energy back and forth and coming to each other’s aid in moments when it all becomes much to bear. Some of the show’s most powerful moments arise in the quartet’s biting send-up of the distinctive blend of racism and misogyny internalized by certain Black British men. The characters they’re sketching here have sharp, specific edges — they’re funny and they’re really not. Ultimately, they spur the show’s most devastating question: “How did you become my biggest oppressor?”

From Queens of Sheba.

Photo: Lawrence Sumulong

It’s snowing! And the trains are askew again, though nothing crashed this time. Eventually, I have to run outside and catch a Lyft in the now completely unmagical freezing rain, and it gets me to the Abrons Arts Center with a whole five minutes to spare. (Thank you, Wenhua!) The place is packed for this house is not a home by Nile Harris. I don’t know what I’m in for, and the answer is: A LOT. Harris trained as an actor, and he throws his body into the show — but/and, he’s also an ambitious writer and deviser, a Black artist with a whole kettleful of biting, boiling, truly gonzo theatricality that’s equal parts deadly serious and gleefully self- (and everyone-) mocking. This is the kind of show that causes second-degree burns.

From this house is not a home.

Photo: Alex Munro

As the performance begins, two skinny, dead-eyed white girls in frowsy Gen-Z fashion statements drape across each other on a slowly rotating platform out in the audience. They pass a vape back and forth and slouch bonelessly. Meanwhile, we hear two voices — Black, male — chatting in voiceover. They casually discuss irony, meme culture, leftist laziness and self-sabotage and hypocrisy — also Black identity and agency online, and the un-cancellability of the alt-right. “I just think,” says one, “ironic Blackness needs to take up digital space or whatever.” Meanwhile, the white girls start whining monotonously into their lav mics: “I’m booored.”

The blasé, brazen, super-pomo tone is just one of the show’s masks, and Harris peels them all back in layers throughout the performance. Truly, there’s nothing “or whatever” about this house — it’s a howling, gutsy, angry, mournful, mess-making, shit-taking act of trolling. You can feel Harris both flipping off and diving right into the eras-long tradition of white experimental artists getting all sorts of fancy grants to do, you know, whatever as long as it can be billed as “radical” — and you can feel his hunger and admiration, underneath and inside the ruckus, for truly radical work. (Can it even be made inside a nonprofit institutional framework, he asks?)

The show is also a wake. Harris’s friend and collaborator, the artist Trevor Bazile, died suddenly in 2021. Together, the pair had come up with the idea for a wild performance featuring a bouncy house, and — using Peter Thiel’s money — they bought one. (In the voiceover prologue, one of the voices muses about bringing it to a George Floyd protest. “Maybe we can get everyone to bounce for Black Lives,” it says with a mordant giggle.) Now, though the house may not be a home, Harris has given it one onstage, where it represents all sorts of other things — from the stormed Capitol to any number of floppy, self-congratulatory liberal-arts institutions. It’s a weird, childlike playspace, part innocent and part grubby.

Sometimes, this house really does feel like the Pop Rocks– and bath salts–fueled creation of three wily kids in a tree house: Harris — who performs as himself and in a variety of literal masks, including an extremely sinister gingerbread-man costume — is making parts of the show up as he goes along, with the help of two close collaborators and fellow performers, the dancer Malcolm-x Betts and the performance artist Crackhead Barney. (If you don’t know her work, try falling down this rabbit hole for the next hour.) Barney rages through the space, nine-tenths naked, smeared in white paint and wearing a chaotic blonde wig, asking old men in the audience if they’re Zionists and hollering for the ASL interpreters near the stage to sign things that I probably can’t put in print. Just as Harris is, among other things, satirizing minstrelsy, Barney is doing a slathering, filterless, singe-your-eyebrows-off send-up of the white lady who can do and say whatever and get away with it. She, and the show she rides in on, are fucking fearless.

Today I’m headed to Mabou Mines/PSNY for Open Mic Night by Peter Mills Weiss and Julia Mounsey. It’s honestly embarrassing that I haven’t seen a show by this fascinating pair yet. I’m still kicking myself over missing while you were partying and 50/50 old school animation (I wasn’t living here, but still), and I’m excited to see what they’ve created this time.

In a small black box at PSNY, the audience is set up in two steep banks, facing each other with a narrow performance aisle in the middle. There’s a stool, a stand mic, and a sound console at one end, a folding table and chair at the other end with a laptop, a lamp, another mic. I know enough about Julia and Peter to know that their work incorporates and blurs the edges of their own identities — they’re entirely present in it, curious about each other and unsparing of themselves, subtly experimenting with truth, persona, and shadow. I’m calling them Peter and Julia because that’s what they call each other; that’s how they introduce themselves. Mills Weiss and Mounsey just seem … not quite right.

I love the show. It’s dry, funny, and very tender — perhaps surprisingly so, given some of Peter and Julia’s work, but, considering the story they’re telling this time around, not surprising at all really. Open Mic Night is a eulogy for an imaginary illegal DIY performance space. You know the place, even though it never existed. In my head, it was in Gowanus, though it could have been in Bushwick or Sunset Park or maybe even the Lower East Side. “Over 10,000 beers were illegally sold there,” Julia tells us, delicately hunched over her mic at the folding table, her mouth right up on it, her voice low, measured, and patient (it, and her face, are at once calm and mesmerizingly unreadable). She also tells us that this space is where she met Peter. “He was attempting stand-up,” she says, without inflection. “It was kind of … only crowd work.”

From Open Mic Night.

Photo: Ian Faria

The middle section of the show gives us a taste of Peter’s crowd work — frenetic, bizarre, seemingly abrasive but actually really generous, and very funny. Wearing her neutral mask, Julia helps keep him on track, hitting sound cues at her table to encourage him or push him to the next bit. “Peter,” she says softly into her microphone, “you seem really tense. I think it’s putting people off. Could you try to relax?” In his own mic, Peter’s breath shudders as if he’s holding an invisible jackhammer.

Ultimately, the show is a gorgeous, unsentimental eulogy to a space that may not have been real, but to an ethos that was — that perhaps still is … But if so, why do we find ourselves mourning it? At a break in the show, I give Julia $5 and take a Coors Light out of a plastic cooler. This is the ethos: curiosity, honesty, experiment, failure, ambition, fellowship — and a break for cheap (and perhaps illegally sold) beer. By the time I head back out into the cold, damp East Village night, I’m homesick for a place I know very well, and have never been.

My night’s not over though. I’m headed down — way down — to Fidi to catch my first show at the brand new PhysFest, which is all taking place at the Stella Adler Studio of Acting. (It’s wild that even established theater institutions can feel like they’re squatting — on the street, the building looks entirely like a massive swanky food court and condo complex for finance bros. Don’t tell anybody there’s an acting school on the second floor!)

The show is War & Play: A Clown Odyssey of Survival, devised by SMJ (who directs), Ania Upstill, and Danielle Levsky, who both perform. (Levsky is a critic-turned-clown; it’s good to know there are opportunities for growth in this career.) Upstill and Levsky play a queer Ukrainian clown couple whose lives are upended by the Russian invasion. The show is largely nonverbal, but every so often we get projected news footage of the devastation in Ukraine, statistics of casualties and displacements (and, at one point, a narrated shadow-puppetry show of an old folktale). Watching the clowns search for missing friends, scurry from one temporary safe place to the next, and try to maintain some small sense of joy amidst the destruction, I feel ill over how little I’ve even heard about Ukraine lately, even though it’s still on fire.

The highlight of the show for me is its third performer, Mariko Iwasa. Iwasa is a physical comedian from Japan who’s toured with Ringling Brothers and now works with the Bindlestiff Family Circus and as a hospital clown. As Levsky and Upstill’s lovers cling to life and each other, Iwasa dips in and out of their story, variously as a street performer, an old friend, a soldier, a refugee camp worker and more. She’s a delightful presence — light and specific, eager without being cutesy, her body both meticulously controlled and very free, her face serious but open. It’s strange, but she reminds me of my grandmother, who, as a young woman, wanted to be a comedian. I head home thinking of her, performing stand-up in a room full of soldiers a long time ago, during a different war.

[ad_2]

Source link